Her actions shed light on the tragic reality of life in the poorest parts of Hungary and caused a true media frenzy.

The year was 1919. The villagers of Átokháza (now called Ásotthalom, near Szeged) were sleeping peacefully in their homes. Suddenly, farmer István Börcsök awoke to the sound of his horses’ neighing. Suspecting that something was amiss, he grabbed a lamp, ran outside, and came face to face with a man he thought to be a thief. They got into a fight and then, suddenly, another man threw a rope around Börcsök’s neck, strangling him to death in front of his wife and son.

The truly shocking part came afterwards. They dragged the corpse into the house and hung it from one of the rafters. Then, at the wife’s request, it was moved to the pantry. A chair was placed nearby, positioned exactly as expected in a suicide case.

The freshly widowed Mrs Börcsök and her son drank to his death, along with the murderers.

The man who had strangled Börcsök was even invited to live with them, according to confessions heard at his later trial.

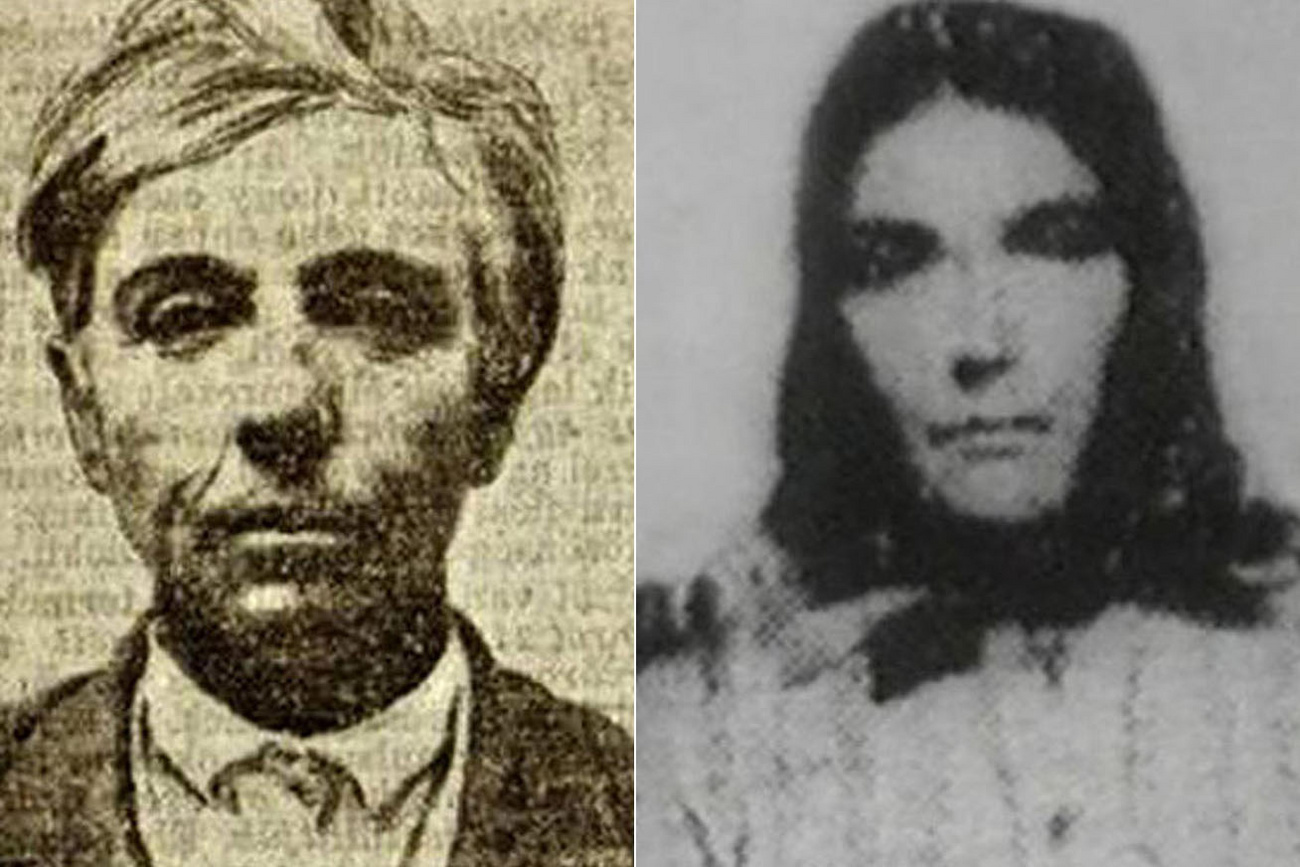

The man in question, who went by the name of “Pipás Pista”, was, in fact, a woman. Born Viktória Fődi in 1886, she was married off at the age of 17 to a much older man named Pál Rieger. Not much is known about her life with complete certainty. Some sources claim that her husband was abusive towards her, just like her father, some others discredit both statements and say that she simply yearned for freedom and better living conditions. Whatever happened, she eventually left her husband and started looking for work. Being of strong build and having smoked since childhood (her moniker, Pipás Pista, could be translated as “Steven with a pipe”), she could easily disguise herself as a man.

Whether this was a matter of gender identity or simply a ploy to gain riches is still unclear. She took on various jobs, such as ploughing or pig slaughtering, and spent much of her free time drinking at pubs. In 1916, she met István Börcsök, who offered her a job on his farm and ended up becoming her first victim. Börcsök’s wife, who had suffered a lot at the hand of her alcoholic and aggressive husband, set her up to the murder.

Three years later, in 1922, Pipás Pista killed another farmer, by the name of Antal Dobák, and this was the case that eventually led to her capture.

Even though she is said to have been responsible for the death of over 30 men,

the gendarmerie did not seriously concern themselves with suicides committed in rural areas. They only discovered that there was something sinister going on when they were called to a dispute between lovers in 1932. The officers separated the parties and escorted the woman home who told them that Antal Dobák had not taken his own life. She had heard this from her lover, who had previously been involved with a relative of Dobák.

At the 1933 trial, which turned out to be a true spectacle, attended by crowds of onlookers, Pipás Pista was condemned to death. The legend says that she was hanged using the same piece of rope that she had killed with, but in reality, she had a different fate. Her sentence was modified a couple of months later to lifelong imprisonment by no other than the regent of Hungary, Miklós Horthy, and she died in prison 7 years later, suffering from lung disease.

Despite her gruesome deeds, her reputation is apparently not completely negative: you can even find a small statue of Pipás Pista if you visit the Bory Castle in Székesfehérvár.

Back in 2015, the mayor of Ásotthalom, László Toroczkai, went further: he spoke about how he would like to turn the figure of Pipás Pista into a tourist magnet, attracting visitors to the village, similarly to how the story of Dracula draws crowds to Transylvania.

Sources: Tamás Bezsenyi: “The First Female Serial Killer in the Kingdom of Hungary” (A chapter in the book The Spectacle of Murder: Fact, Fiction and Folk Tales), Egyperces krimi, Szegedi Lap, Szeged Tourism, Délmagyar