Every year on the 22nd of July, a special feeling overwhelms Hungarians while they hear the noon bell toll. On the 22nd of July, in 1456, 564 years ago, the siege of Nándorfehérvár took place. Thanks to the triumph of the Hungarians and the help of some other European forces, the armies of the Sultan Mehmed the II. had to withdraw. The popular Hungarian belief is that the victory of János Hunyadi was a “world-renowned” triumph, which commemorates Hungarian courage forever. Hunyadi was the archetype of the Hungarian hero in every era, and his actions belonged to the most glorious pages of Hungarian history.

The historiography of the 20th century has washed a little colour away from his myth in many ways, yet it has not taken deep root in public thinking. Although it turned out that János Hunyadi was responsible for launching the tragic campaign of 1444, he lost his two most significant battles and took an active part in the civil war, but all of this did not detract from his appraisal as a national hero, as his successes were attributed to his personal qualities.

There are two things: real deeds and their judgement, and these two are very separate things. The latter, of course, plays a more important role in creating a tradition.

Such was the case with István I., Mátyás Hunyadi and Lajos Kossuth, who were seen by their contemporaries and immediate descendants with much less empathy. Yet, newer generations their stories in a way that evokes devotion and heroism. This is not a bad thing, however, because it can inspire future generations, but it is important not to alter past events entirely.

For us Hungarians, in the last five hundred years, Nándorfehérvár has become a symbol of self-sacrificing heroism, Hungary as the bastion of Christianity and the feeling of ‘we must fight alone’.

However, this developed gradually over the centuries. For those who fought the battle, this was certainly not as clear as it has become a symbol to us. But in today’s highly relative world, where centuries-old beliefs and values are being questioned in a matter of moments, we need to see how successful the Christian triumph really was.

The young Sultan Mehmed II. who inherited the Ottoman throne in 1453 successfully invaded Constantinople, a city that symbolised the last light of the Roman Empire. This was unthinkable for the people, and it caused panic in Europe. This was the context in which the Hungarians fended off the invaders at Nándorfehérvár. An attack launched by a young and ambitious Sultan against a divided force that lacked confidence.

It is also important to note that the fall of the Kingdom of Hungary would have dragged the remaining states of the Balkan Peninsula with it, so the eyes of the West were gazing upon Mihály Szilágyi and János Hunyadi whose defences were tested to the very limit.

Luckily, almost everything fell into place perfectly for the defenders: Serbian forces broke through the Ottoman ships on the Christian side, and the untrained Christian forces led by János Kapisztrán (John of Capistrano) intervened just at the right time. But there was more luck to it than you would first guess.

All things considered, the Christian victory, was unexpected and seemed miraculous in the eyes of contemporary people, so it was obvious to incorporate self-sacrificing heroes and miraculous elements into the narration of the story to give it some extra flair. This is how the myth of the noon bell toll and the heroic Titusz Dugovics came to life and became an integral part of Hungarian belief and tradition. Now it can be scientifically proven, that they cannot be associated with the triumph of Nándorfehérvár.

However, all this should not bother us, let us also rejoice in the bell ringing at noon and tell our children about the heroism of Titusz Dugovics, because these beliefs are the ones that bind us Hungarians together, these beliefs help us through hard times and these figures of heroism inspire us.

The noon bell toll

To this day, many stubbornly believe, that the noon bell is in memory of the triumph of Nándorfehérvár, even though this theorem has been refuted several times over the past decades. Callixtus III., when found out about the Ottoman campaign, issued a so-called ‘imabulla’ (papal prayer bull) in Rome on the 29th of June announcing a spiritual crusade to defeat the “unbelieving”. According to the bull, between three o’clock in the afternoon and the evening prayer, they would ring the bells three times at half-hour intervals, and that every Christian would pray fervently when they heard it. Also, a bad omen appeared on the sky around this time on the 3rd of June; Halley’s comet, which suggested destruction and danger further making it seem unlikely to be able to stop the Ottoman Empire. The news of the triumph of Nándorfehérvár only arrived in Rome on the 6th of August, and to his delight, the Pope set the Feast of the Transfiguration of the Lord on this day, so in fact, this moment is the one which is most strongly associated with the Hungarian victory, not the noon bell toll.

It is important to mention that the bull and the victory in Nándorfehérvár were forgotten in the second half of the century. Due to the growing Ottoman threat, however, Pope Alexander VI. renewed the bull of his predecessor in 1500 and issued a new decree. He changed two things in the papal decree: he ordered the noon bell toll to encourage prayer, and this decree is the reason why they toll the bell at noon in the Christian world. So, we can only talk about the noon bell toll in the Christian world from this point onwards.

We know from the research of Endre Pálvölgyi that the idea that connects the noon bell to a Hungarian event developed in the Hungarian public consciousness in the middle of the 19th century.

It can be seen from many examples that official cultural policy, with the help of historical science, planted this dogma in the Hungarian public thinking during the millennium celebrations at the end of the 19th century. In a Hungary struck by the Treaty of Trianon, it did not take much to start believing it. The bell-ringing on Hungarian radio spread this myth among Hungarians, and it seems that it will stay with us in the future as well.

Titusz Dugovics

It is no exaggeration to say that almost everyone in Hungary knows the story of Titusz Dugovics. I was greatly moved by his sacrifice when I learned about him in 3rd or 4th grade, but unfortunately, it turns out that this is only a myth as well. The painting of Sándor Wagner beautifully depicts the story of the castle-defending hero, who on July 21st, 1456, dragged down with himself a Turkish soldier trying to raise the Sultan’s flag from one of the towers of Nándorfehérvár, kindling the spirit of his brother in arms. However, only a few people know that Titusz was actually born in 1824 when Gábor Döbrentei published three diplomas in ‘Tudományos Gyűjtemény’ (Scientific Collection) which were in possession of the then jury of Vas County, Imre Dugovics. In the following decades, the claim of the famous literary man was more and more widely accepted, so until the 1990s no one questioned the existence of Titusz Dugovics, but then more and more people raised doubts about Döbrentei’s claim.

The figure of the self-sacrificing hero is actually a migratory motif found in Western literature since the Antiquity.

Antonio Bonfini was the one who recorded the event the first time connected to Nándorfehérvár, but in his recordings, the soldier had no name. The next time such a hero is mentioned was by Johannes Dubravius, born in 1552. He refers to the self-sacrificing soldier as a Czech knight. At the beginning of the 19th century, the hero’s name became János Körmendi in the ballad of Johann Karl Unger. The cult of Titusz Dugovics was started by Döbrentei who believed the forged documents of a noble of Vas county were real. We do not know what motivated Imre Dugovics to forge these documents. It might have been to stop rumours around the nobility of his family, or he just simply wanted to have heroic ancestors. However, all this is irrelevant, as in the era of national romanticism there was a considerable demand for self-sacrificing heroes, so personal ambitions were immediately placed in a national context, and the cult of Titusz Dugovics was born.

János Kapisztrán (St. John of Capistrano)

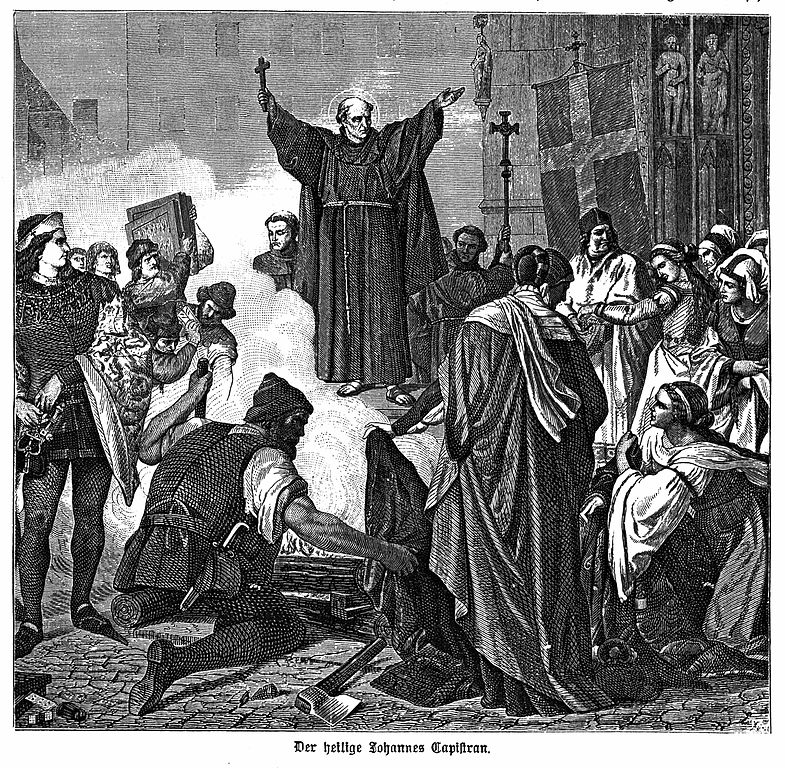

After the fall of Constantinople in 1453, the Pope sent János Kapisztrán (St. John of Capistrano), who was approaching his seventies, to gather crusaders against the Ottoman Empire with his fanatical enthusiasm. He arrived in Hungary in 1455 and established a Christian alliance against the Turks. In the Spring of 1456, he enthusiastically began to recruit crusaders again.

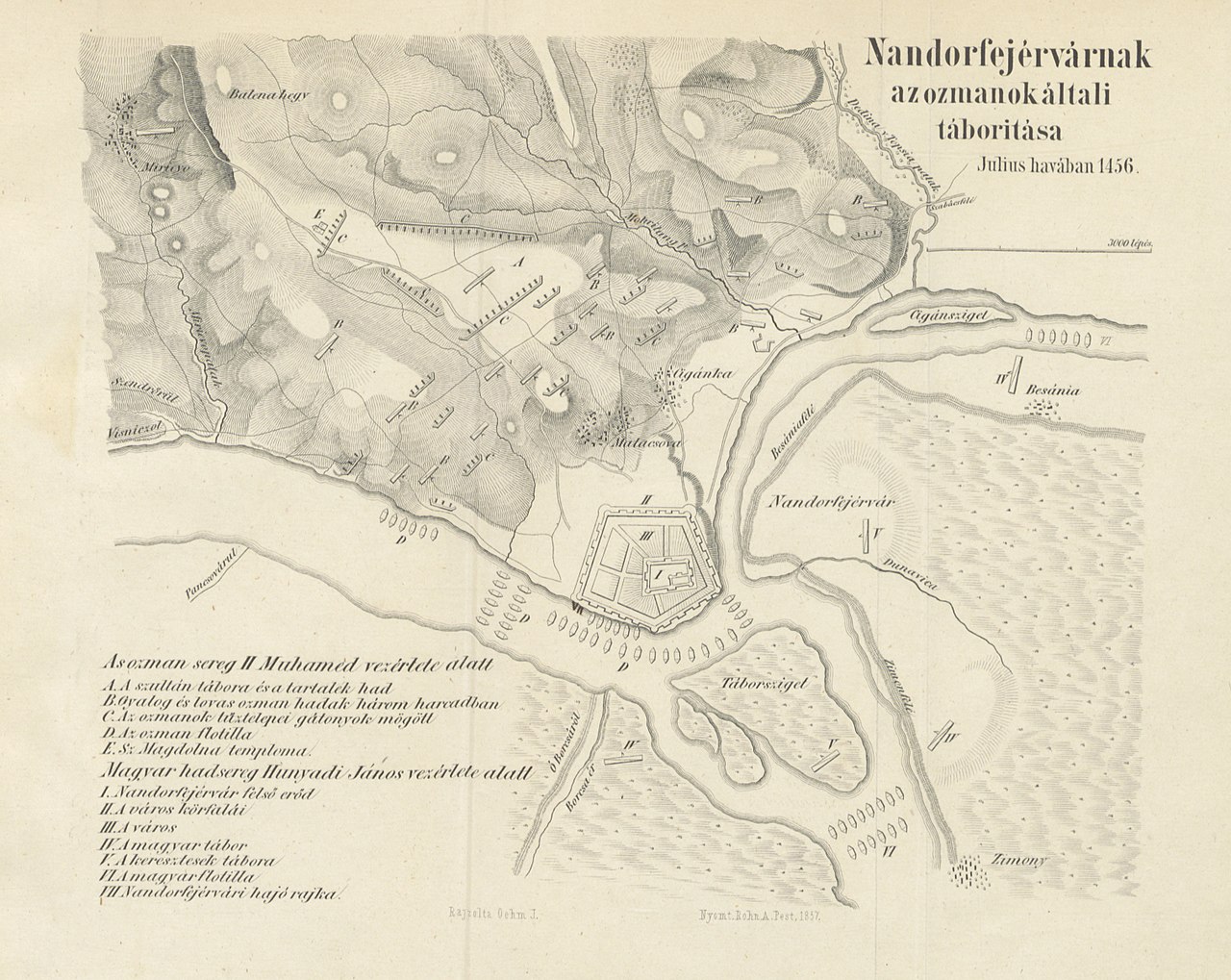

He managed to gather an irregular army and hurried to the camp of János Hunyadi in order to aid him and his forces to defend Nándorfehérvár. After the fleet of Hunyadi broke through the ships of the Turkish Admiral Baltoglu, he sent Kapisztrán and his units to the island of Száva. Hunyadi and his mercenaries marched into the castle, to help the defenders, led by Hunyadi’s brother-in-law, Mihály Szilágyi, who found it difficult to keep their positions within the shattered walls of the castle. The sultan sent his army in to attack on July 22, but the defenders were able to fend the elite Turkish units off one last time.

The decisive clash was triggered by accident, however. Kapisztrán’s force was made up of undisciplined troops, and some of them crossed the river and began to attack the enemy camp from the flanks. More and more of these irregular troops followed suit and the Turkish Sipahis and Janissaries gathered to make a counterattack.

When Kapisztrán realised this, he wanted to prevent the clash, so he boarded a boat, but he achieved the opposite effect. His soldiers believed that their leader is inciting them to attack, so they followed his example and clashed with the Turks.

The Ottomans were surprised and left their camps and artillery unattended. Hunyadi seized the opportunity and broke out of the castle with a cavalry assault and seized the artillery pieces and attacked the Turks with their own weapons. A short, bloody conflict ensued, and the Hungarian forces emerged victoriously.

Shall we call it Belgrade/ Beograd ?

We shall not call it Belgrade/Beograd.

That would be confusing and anachronistic. It would be different than how other historical place names are treated (Constantinople, Leningrad, Bombay, etc…). Since this is a Hungarian historical event on a Hungarian page and your suggestion is inconsistent with other historical references, shall we call your suggestion trolling?

I disagree with Arpad. If you write in English, especially, but not only, if readers are mostly foreigners and the News portal is in English, city names should be written in English. Non English names are acceptable in exceptional cases, which is not the case of Belgrade, for nobody but Hungarians know what Nandorfehervar is. This particular event is known, internationally, as the Siege of Belgrade.

I am sure that Hungarians would not like it if an article referred to Szeged as “ Seghedin “ . Just an example…

Mario, if it was written in Hungarian history, and this being a Hungarian web page written in English, the historical names should read as such. The commonly used new name can be stated in brackets. Pozsony(Bratislava), Becs(Vienna), Orosz(Russian) Lengyelorszag(Poland) for example. What is correct to Hungarians and historical should not be be changed or bastardized because of foreign readers.